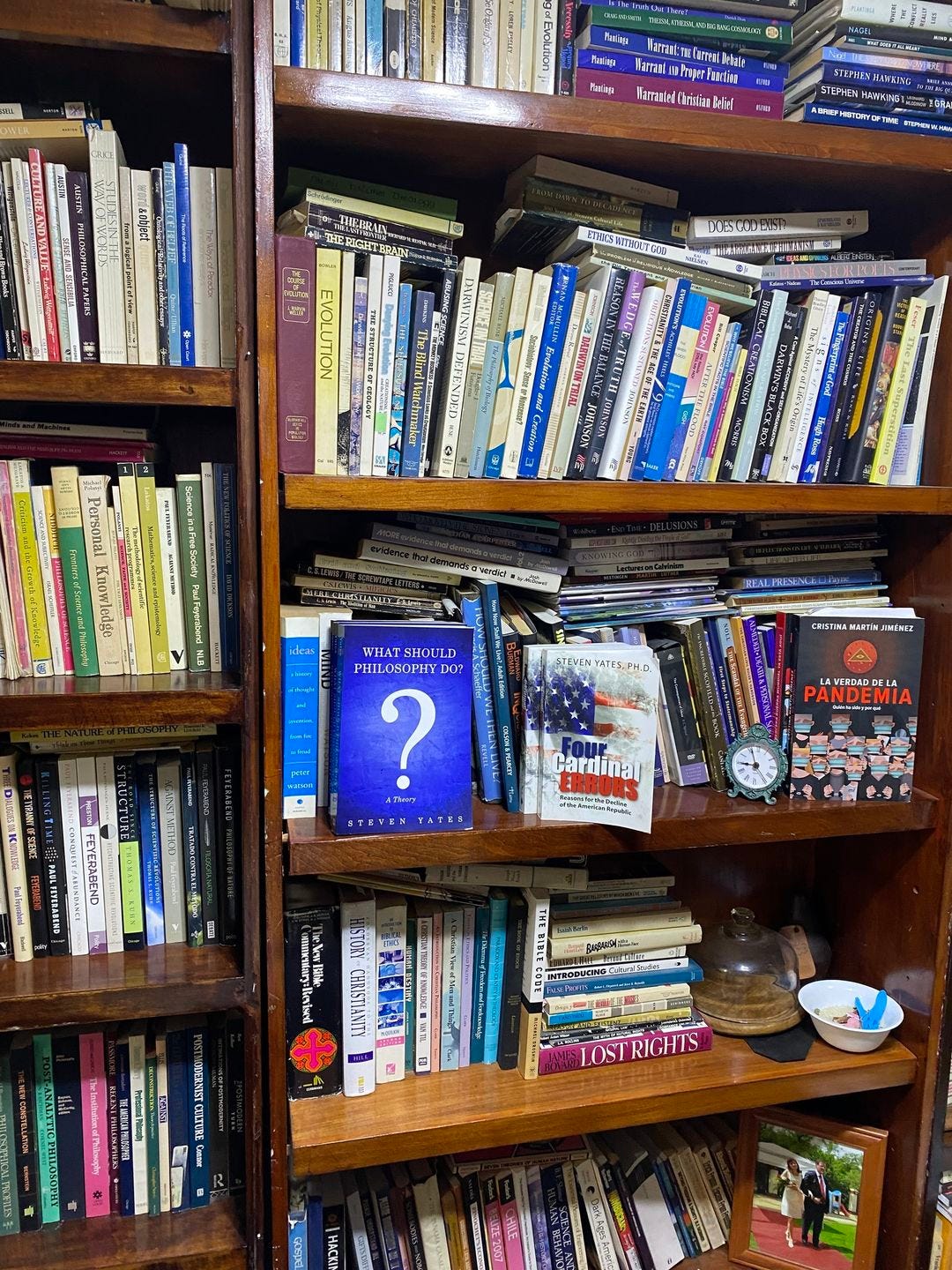

On My Book, "What Should Philosophy Do? A Theory" Part II

What is the Real Great Replacement, and what has it done to our civilization and to the world?

Part I. [Author’s note: I’d hoped to have this up sooner but ran into some organizational problems I hope are resolved, as much as is possible with a project like this. Then came some other workaday issues I had to attend to that led me to drop it for a couple of days and then come back to it. It’s finally ready.]

Worldview Change Is Not “Rational”: Some Basics.

The basic beliefs of a worldview are not likely to have been acquired “rationally” and are not held “rationally.” What does this mean, and what does it imply?

Rationalism, understood broadly, is the idea that human beings have a faculty, called reason or rationality, that alone searches for, finds, recognizes as such, and justifies assertions of what it calls The Truth — that this faculty is what makes us human. Aristotle: “man, the rational animal.”

Eighteenth century Scottish philosopher David Hume criticized this idea. In his Treatise of Human Nature (mentioned at Part I’s outset, it “fell stillborn from the press”), he argued convincingly that rationality — reason — can never motivate action. As his primary interest was grounding ethical action outside of religion, he argued that such actions were motivated by sentiment and habit, not reason.

Most psychologists today would probably agree, however they qualified this. We are not “rational animals” with emotional add-ons needing to be controlled. We are emotional beings who sometimes reason if we choose to do so. It is not our “default setting,” which is why we see so little of it if we’re being honest.

What about this curious idea, The Truth?

As matters have played out in modern, recent, and contemporary philosophy, there are many, many theories of The Truth. Correspondence? Coherence? A complete and consistent description of the world (might be impossible for Gödelian reasons)? Others? Most raise more questions than they answer, so much that some recent philosophers (Richard Rorty is the best example) have thrown up their hands in despair. They’ve described the idea as hopelessly mired in confusion and urged us just to drop it. (See Rorty’s Contingency, Irony and Solidarity 1989).

The idea of The Truth (not to be confused with commonplace truths like “grass is green,” “the cat is on the mat,” “7 + 5 = 12,” and “peace is better than violence”), has its roots in Platonism, which posited an Ideal Realm of Forms or Universals where The Truth resides. The Truth, Platonists insist, is apprehended by the human intellect, which possesses an Ideal Method of finding it. For early Platonists this was Mathematical Reason, one might call it. In today’s positivist-influenced environment it’s called Scientific Method (or The Science).

In these multiculturalist times, it’s surprising such ideas have survived! But they have!

Most materialists (except for postmodernists like Rorty) have retained the basic idea of finding The Truth via The Science.

In his controversial Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge (1975), Paul Feyerabend criticized The Science (in his day, pre-Fauci, just the idea of a single, binding “scientific method” that defines science and explains all scientific progress) as an illusion. He drew on a wide range of cases inside and outside the sciences. The key philosopher behind his analyses was Wittgenstein (not Popper!) and such notions as “forms of life” and “family resemblances.”

I understand the temptation behind The Science. As enterprises, the sciences have been reasonably successful, especially when practiced honestly and not hijacked by governmental or corporate interests — in which case they became “successful” in a different way!

I would argue that the success of physical science and its technological applications are not dependent on a worldview. They fit equally well with either Christendom or materialism, neither of which is held “rationally.”

Why do we say that the fundamentals of a worldview are nonrational? One reason is that they cannot be proved: established with deductive certainty. Attempts to do so founder, and only invite skepticism. Frequently the idea of what counts as proof is embedded in a worldview, leading to circular reasoning.

The principle of noncontradiction stood at the foundation of Aristotle’s philosophy. Aristotle, likely one of the most acute thinkers of all time, understood that he could not prove the principle of noncontradiction (roughly, that a thing could not both “be” and “not be” at the same time and in the same respect) because the very idea of proof presupposed it. So in Book IV of the Metaphysics, he gave a “negative demonstration” instead. He argued that if we did not posit the principle of noncontradiction as given, it became possible to use language in a contradictory fashion, “prove” anything whatsoever, and discourse itself becomes unintelligible and useless.

Something similar can be envisioned as standing at the foundation of a worldview — any worldview. Hence the Kierkegaardian “leap” at the foundation of his understanding of Christianity: stop with the attempts to “prove” that God exists, and His existence comes out and becomes manifest! Presuppositional apologetics argues that atheism leads to incoherence.

So why is a worldview believed? It is not something a philosopher dreamed up and outlined in a treatise, although obviously worldviews can be written out and often are, in some form. A worldview is embraced because it supplies life’s answers, often in ways that bring happiness and joy as well as stability in a community. An ensuing generation will grow up with it and into it, “immersed” in it. Eventually it does not occur to them to question it. In other words, worldviews are accepted for ultimately nonrational reasons; support for them is indeed based on sentiment and habit, not logic. This is not to say that reasons cannot be given for a worldview. But those reasons are neither decisive, nor basic. In the last analysis, worldviews are believed on emotional, not rational, grounds.

This is the case whether the worldview makes that “leap” to God’s existence however described, or whether it denies this and demands a hard materialism in which the only reality is the one we experience through our five senses or discover through the sciences.

Materialists may assume, but cannot prove, the existence of something called matter: “corporeal substance” (Descartes), a “something I know not what” (Locke), a sort of substrate underlying the “primary qualities” of the objects of our experience (Locke), but superfluous and able to be gotten rid of (Berkeley, Hume).

When we consider the findings of modern physics — or physical systems — and then recent microphysics (atoms, subatomic particles, quarks of at least six types suggesting component “smaller” micro-microphysical systems), spatiotemporal physical reality certainly seems to be systems “all the way down.”

Where’s the “matter”?

Materialists will find this frivolous, of course, and contend that we encounter “matter” every time we brush up against a physical object. The desk my computer is sitting on as I type this “resists” if I try to push my index finger through it. That’s because the desk is made of matter, they will say. So is my finger.

I’m reminded of Dr. Samuel Johnson’s kicking a stone and claiming he had refuted Berkeley’s subjective idealism (the first modern metaphysical system to get rid of “matter”).

It is such “refutations” that are frivolous and unserious.

Microphysics has a quite clear explanation of what is going on when the desk “resists” my finger. It involves the behavior of microphysical systems, not something called “matter.”

But isn’t the Christian God in the same boat?

Christian theists see at least some personal psychological and social benefit to belief in the Christian God, the idea that He expects certain things of us and that we should refrain from other things, and of surrounding rituals, even if we can’t “prove” His existence, and even if the rituals can be abused.

I am unsure of the benefits of either a belief in something called “matter” or in the conception of nature that materialism posits. And as we’ll see before we’re done with this series, materialism has been abused aplenty!

Worldview Change as a Real Great Replacement. (And: Cultural Marxism Revisited.)

So much for all the intellectualizing. The primary argument of What Should Philosophy Do? is that philosophers should identify, clarify, and evaluate worldviews — based on their effects on society, within culture, and on the trajectory of civilization.

The secondary argument tries to apply this by producing such an analysis. It concludes, among other things, that the Christian worldview (in whatever form) was replaced by the materialist one (in whatever form).

I now call this the Real Great Replacement, a phrase I’d not thought of when writing What Should Philosophy Do?

Now if a worldview’s basic propositions are not embraced “rationally,” it’s highly unlikely that worldview change is going to be a rational process. Even if there may seem to be solid reasons for it. The worldview change we’re interested in here occupied a long period of time (well over two centuries). It involved many thoughtful philosophers, investigators, and authors, with significant mileposts along the way. The arrival of Darwin’s naturalistic theory of the origin of biological species including humanity was surely the most significant of these.

Modern materialism as a worldview began its slow rise in the 1700s with several Enlightenment philosophers such as Denis Diderot and Paul-Henri (Baron) D’Holbach. Comte’s positivism essentially declared metaphysics to be replaceable by empirical science, and the embrace of positivism in philosophy and in the rising social sciences (sociology, psychology) over ensuing decades rendered such discussions as this one null and void for decades. Darwinian evolution arrived on the scene, with aggressive and able defenders such as Julian Huxley (“Darwin’s bulldog”).

Materialism thus took over intellectual centers (major universities) by 1900. It seeped outward to the rest of Western culture via a sort of osmosis, led by “public opinion” on matters scientific, economic, literary, artistic, and even theological where Machen commented on its effects on his Christian denomination. Materialism manifested itself in the arts, in music, in literary products, and eventually lifestyle choices. The former of these grew increasingly nihilist (think of Dadaism, or absurdist plays such as Beckett’s Waiting for Godot). The last had begun to embrace the hedonism of drugs and sex by the 1950s (think of the Beat Generation; Alfred Kinsey — a hard materialist’s hard materialist! — had opened the door to a sexually “liberated” culture with his infamous studies published mid-century.

Cultural Marxism piggybacked on this, starting in the U.S. with Marcuse’s essay mentioned in Part I. By the time it became influential, the Real Great Replacement was all but complete (among its last strategies was removing organized prayer from public schools). What I call the death culture would be soon in coming. The death culture gained enormous traction with the idea that women had a “Constitutional right” to end the lives of their unborn children by artificial means — abortion.

Cultural Marxists understood at some level, moreover, that worldview change was not rational, and that the cultural changes they wanted would not be rational. Hence aside from a few theorists like Marcuse, they didn’t use philosophical talking points. They turned to mass media, especially television and Hollywood. They recognized that common people respond to images and stories: especially young people. So their minions sought to influence the more impressionable audiences: the younger the better! (Some now call this “grooming.”)

Expanding, and using perhaps the most obvious example: back as the 1980s most people saw homosexuality as something to shun if not revile openly: emotional reactions, of course. But by the late 1990s we saw sitcoms with gay and lesbian characters presented sympathetically in storylines. These characters struggled with the same things, fought the same battles (at work, in relationships, etc.) as their straight counterparts — and they did so entertainingly! Audiences of shows like Ellen (featuring Ellen DeGeneres who had “come out” as a lesbian) laughed with the characters, not at them — an important distinction. Other such shows included Will & Grace and Friends. They were massively popular, and there was more to them than promoting the gay/lesbian element which was integrated seamlessly into larger portrayals of the comic aspects of life. Then, of course, came Brokeback Mountain.

That was 2006. Attitudes toward homosexuality had shifted. Revulsion had been replaced by broad acceptance and even fascination.

And if you weren’t on board with the cultural shift, you were homophobic.

Some of us pointed out that this was a linguistic trick: propaganda, in other words. A phobia is an irrational fear. But those who resisted the shift did not do so because they “feared homosexuals,” but because they rejected homosexual conduct on moral and sometimes public health grounds (studies had already shown that homosexual men in particular tend to be much more promiscuous than heterosexual men, don’t use protection, and so their lifestyle becomes a breeding ground for STDs).

That’s a didactic response. Hence it is ignored or deconstructed as self-deception or labeled as “hate.”

The 2000s and then the 2010s became an era of “phobias” which now include “transphobia.”

In 2015 we got the Obergefell v Hodges decision in which a then-liberal Supreme Court “found” a “right” to same-sex marriage in the Constitution. (See what I did there? Two can play these verbal-psychological games.)

The tipping point had been reached long before. The larger worldview change, as already noted, was complete except at society’s margins (many rural populations, and “fundamentalist” Christians; although Muslims, too, reject homosexual conduct, and with much greater violence!).

One moral system, that of Christendom, had mostly collapsed. Another — subjectivist, hedonist, and “do your own thing” individualist — had replaced it, including in powerful corporations. Its predecessor was branding as backward and authoritarian. Think of the many televised storylines going back as far as the 1980s in which Christian believers are depicted as obnoxious bullies or even as criminals.

If you need another concrete case study of a sweeping cultural Marxist change, contrast the 1619 Project, highly touted in academia and at the center of critical race theory (source of the idea of “systemic racism”), with the traditional image of the American founding. For the latter, ideas mattered, not the fact that the American founders were all landowning white males, some being slaveowners.

Many of those ideas, such as free speech and due process, are now gradually disappearing! I’ve a sense Elon Musk was fighting a rear-guard action when he bought Twitter and proclaimed the platform an online free speech zone. The leftist “Twitter mob” simply went elsewhere.

Think about the different ways of viewing the world these different perspectives offer, and how we arrived where we are now. To those with the traditional view, now limited to conservatives (not to be confused with neoconservatives!) and some libertarians, the devastating conditions in the black community represent 50 years of left-liberal (cultural Marxist) failure.

But to critical race theorists, this condition manifests the intractability of “systemic racism” against mere reform. Marxism in any form is revolutionist, of course, not reformist. This should be kept in mind when asking what critical race theorists want.

The original civil rights vision based its ideals of racial equality — nondiscrimination, equality before the law, equal opportunity — on the idea that we’re equal in God’s eyes: whether one believes the American founders gave us a republic rooted ultimately in Christendom or a secular state (supposedly) not rooted in any worldview. Christianity’s philosophical anthropology is that we’re all equally sinners in need of redemption. What makes racial equality a just cause — equality of opportunity, not necessarily equality of result — just is our being equal in God’s eyes. If one reads the writings and speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., one sees that they are permeated with religious references. That is because Dr. King was a theist, not a materialist.

Critical race theory doesn’t attack or denounce belief in God as such — that I know of (I’ve not studied it exhaustively). It doesn’t appear to wade into metaphysics, instead assuming such problems to be solved. As the 1960s theologian Harvey Cox said of secularism generally in his enlightening The Secular City (1965), it simply “bypasses” such matters and “goes on to other things.” It focuses on social conceptions of race/ethnicity, promoting the Marxian idea that these are “social constructions” integral with arrangements that “oppress men and women of color” regardless of anyone’s intent, and are manifested as “inequities.” You don’t need to deny God to do this, any more than an evolutionary psychologist seeking to explain why people are drawn more to negative news than positive “feel good” stories needs to deny God explicitly. He simply “has no need of that hypothesis,” bypasses them, goes on to other things.

Hopefully this discussion makes the case that a conversation on worldviews is relevant to the history of ideas (how we got here) and to current events (where we are now). Recent research (Pew) suggests that the Christian worldview is still losing ground. Church attendance is dropping, and the number of people who respond to poll questions asking for religion are marking their response none. In which case, they become materialists by default.

If we get this wrong, much suffering is likely to ensue as I will argue in Part III. A conversation about worldviews might help us answer the salient questions about the future: what we want the U.S. — or the West more broadly — to look like (assuming it survives) in 20 years, 30 years, 40 years.

Or in other words: what kind of society do we want, and what are we willing to do to keep it? If we fail, what do we relinquish? What have we already relinquished?

The Death Culture: Abortion on the Left; Neoliberalism on the Right.

Materialism has underwritten what I call the death culture. This is part of the kind of critique of a worldview I advocate in What Should Philosophy Do? If a worldview systematically devalues human life, sees it as expendable if inconvenient, that weighs against it — or should.

Abortion-on-demand exemplifies a death culture: abortion is easily the most obvious exemplar of ours. Stripped to its basics, abortion-on-demand is the unconditional “right” of women to kill her unborn child. If it isn’t an unborn child, then pray tell, what is it? As a student of mine once sarcastically put it, eons ago when I was able to secure teaching positions, “Well, it’s not a fish!” That came from a female student. She wasn’t an “expert,” obviously. She was going off what her gut was telling her. Strange thought it may sound, I think that a lot of times we can trust our gut. It may offer organic and perhaps subconscious connections to reality that for whatever reason, our cerebral cortexes fail to grasp.

What Should Philosophy Do? (Chapter 4) examines some of the twisted rationalizations so-called feminist philosophers have tried to supply justifying the procedure. Roe v. Wade (1973) gave it Constitutional sanction.

Abortion is hardly the only manifestation of the death culture, however. An economic system also devalues human life if it redistributes wealth and power upwards, as the past 40-or-so years of neoliberalism has done, reaching the point of leaving millions of hard-working people struggling to stave off homelessness.

It may seem odd to bring up neoliberalism after bringing up abortion. Isn’t neoliberalism a target of the left, while abortion is a target of the right?

This is a problem with the left-right political paradigm, not abortion or neoliberalism. For neoliberalism is just a less obvious exemplar of the death culture. At home, it systemically inflates currency, destroying its purchasing power so that what the average person experiences is a massive increase in the cost of living. If that person’s wages fail to keep up with that cost, he or she is soon working two and three jobs to keep up — if he or she can find them. Our society long ago left behind the one-breadwinner nuclear family. When currency loses its purchasing power and wages fail to keep up with the cost of living, both parents must work (if they manage to stay together—a separate issue), leaving the next generation on its own. (As early as the 1980s we were hearing about “latch-key children” who came home from school to empty houses because both parents were working.)

Today the problem is massively worse, and we have a raging homelessness problem in the supposedly wealthiest nation on the planet, while the top .00001 percent, the billionaire class, controls around 50 percent of that wealth.

This has happened because, to paraphrase neoliberalism’s primary architect Milton Friedman (a materialist), the only social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. All else is “externality.” It matters little, moreover, if a combination of corporate policies of built-in obsolescence (forcing consumers to buy another item when the one they purchased little over a year ago breaks), technological change (rendering older products, jobs, and entire occupations obsolete), and globalization (importing cheaply-made goods from China thus gutting American manufacturing) and importing migrants (who will work for cheap and drive down U.S. wages)

Universities have adopted this “business model,” as it is euphemistically called, which is why roughly three quarters of college and university teachers (or “adjunct instructors”) now work off the tenure line and will probably never see academic tenure. Couple this with the cost of getting a university education which, as everyone knows, has skyrocketed over the past 30 or so years, creating a generation (or more) of debt slaves. Part (not all) of skyrocketing tuition goes to fund administrative bloat. This is part and parcel of the redistribution of wealth upwards: the university president and top administrators are paid six figures by their neoliberal institutions while “adjuncts” work two and sometimes three jobs to keep a roof over their heads, the lights on, and food on their tables — while praying for no health or even car emergencies. This continues for as long as they are willing to put up with it (some of us weren’t, a major reason we left academia).

This is the death culture: human lives have no intrinsic value. They only have whatever extrinsic value they can bring to “the marketplace,” i.e., to a corporate entity either as an employer or a consumer, their landlord or mortgage holder (usually a bank), or the government as a taxpayer or as cannon fodder to fight a foreign war of choice.

For if all we are, are big-brained mammals limited to our short life spans, what is to prevent this from being the dominant ethos spreading across the planet, as a very few enrich themselves at the expense of the many because they can?

Why should not the strongest, the cleverest, the most opportunistic, rule over the weaker and more innocent? However reluctant we might be to think of them as wise, Platonistic philosopher-kings?

Why should the latter — or their carefully vetted minions in corporate mass media, in “education,” elsewhere — be bothered to tell the truth to big-brained mammals, be it about inflation or other aspects of the economy, about “democratic institutions,” about their prospects for a better life, or about themselves and their plans for the world?

Is it possible, finally, that the death culture, which regards all environmental consequences of corporate control and (sometimes involuntary) mass consumption by their debt slaves as “externalities,” is damaging the ecosphere of the planet? Yes, it is possible. We’ll return to this point.

Part III to come in a few more days.

Much to disagree with you on as a Voluntaryist, but well written as usual and admirable in clearly delineating difficult and often abstruse academic issues so as to be usefully debated by the non-academic sector. Looking forward to Part 3.