Stale Breadcrumbs from the Academic Dinner Table. (Notes of an Ex-Adjunct)

Notes of an Ex-Academic, Ex-Adjunct

“It’s a Big Club … and you ain’t in it!” --George Carlin, “The American Dream”

“It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.” --Noam Chomsky, “The Responsibility of Intellectuals”

INTRODUCTION

This is one part of an ongoing project long in the making. When, back in 2014, I heard of interest in an anthology of first-hand narratives and other efforts reflecting in one way or another the adjunct experience, I knew that as an ex-academic and ex-adjunct, I could contribute. I was soon caught between conflicting impulses. Should I write something semi-autobiographical about my career trajectory as a member of the academic precariat[1] and add to the growing body of “quit lit”? Or would it be more useful to do a deep dive into the disaster American academia has become?

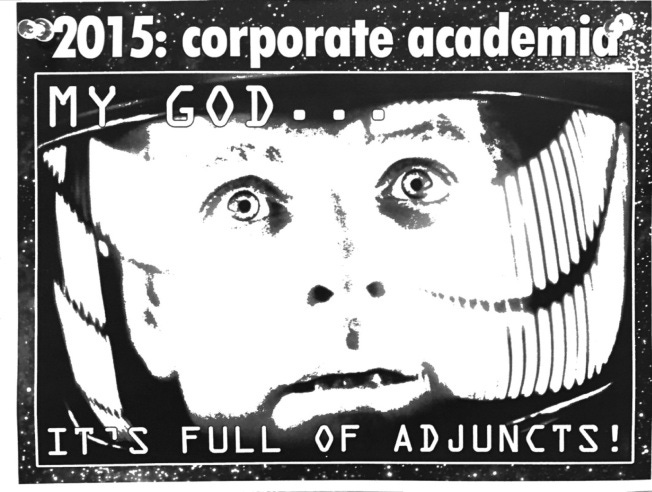

The impoverishment of the New Faculty Majority hasn’t happened in a vacuum, after all. Thoughtful people who trouble to look into the matter soon figure out that a latent anti-intellectualism has long permeated American society from top to bottom. Efforts to socially engineer obedient workers and mindless consumers via public schooling and mass media go back a very long time.[2] And as George Carlin put it in his colorful routine quoted above, it is clear that the real powers behind these efforts, those in the Big Club, never wanted a population capable of critical thinking. Those in the Big Club preferred us to believe it was just market forces at work. Much of “economic science” is premised on this notion. Social engineering efforts began, however, well before that particular permutation of capitalism known as neoliberalism,[3] which beginning around the 1980s began to move us in the direction of a quasi-feudal order in which we no longer have stable careers but rather work at “gigs.” Upward mobility is increasingly difficult, and people are told to continuously “reinvent themselves,” “prepare to have five careers” during their working lives, etc., etc., during their overall “race to the bottom.”[4]

In the techno-feudalism toward which we seem to be heading at breakneck pace, there is the ruling class of neo-feudal plutocrats, their top administrators, and many media, academic, and “think tank” shills. That’s the Big Club!

Then there is the new peasantry. That would be us.

As aspiring scholars and university professors we tilled the fields of the academic “gig economy” and ate the stale breadcrumbs tossed our way from the dinner tables of those in the various academic franchises of the Big Club.

Peasant-level adjunct pay may be as little as $2,500 per course, which may mean bringing in under $20K/yr. after taxes. Since this is an unlivable wage in most urban and suburban environments today, it may mean going into debt to pay the rent and utilities, going hungry so one’s children might eat this week’s Ramen noodles, and praying for no health or car emergencies or other unanticipated expenses.

On the other hand, college and university administrations have seen their numbers swell and their pay explode over the past three decades.

Few adjuncts are positioned to expose and challenge administrative abuse and academic inverted totalitarianism.[5] Attempts to unionize notwithstanding, sometimes with the assistance of official groups like the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), no adjunct organizations have a power base from which to operate.

Some eventually decide not to tolerate it any longer. “Quit lit” is thus everywhere, from platforms like Medium to the pages of The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Scholarship has suffered from the academic culture’s long term decline. In subjects such as mine, the best are now an aging, shrinking aristocracy, retiring and dying off one by one. With rare exceptions, those purporting to replace them — to speak as diplomatically as possible — leave much to be desired!

There are no easy answers — especially with Captain COVID likely to force some institutions to close their doors. Surely there is something to the claim that higher education, rife with perverse incentives as we’ll see, produced — still is producing — too many PhDs. How many were misadvised (as I was) about a coming “turnaround” in the academic job market which never occurred; how many more naively see academia as a refuge from that larger “gig economy” which, as is often said, benefits the “one-percent” and has grown increasingly hostile to everyone else?[6]

Is there anything we can do?

Sadly, resolving the conundrums the adjunct crisis raises is beyond what can be accomplished here.[7] But those of us who put down our peasant’s tools and left the fields did not abandon our ability to think, nor the will to use it. Thus we can still ask questions, point to lies, and perhaps make a few constructive suggestions.

In light of this, the first part below is mostly autobiographical. I tell my story, or as much of it as is relevant. The second part draws in more discussion of the particular “enlightenment” one can cultivate once one accepts one’s status as an outsider, seeing creative potential there. In the shorter concluding section, I discuss a few implications for where higher education’s collapse has brought us as a society. It is a collapse, after all — understanding collapse as a process, not a singular event as in a Hollywood flick. We are nearing the end of this process, where brick-and-mortar institutions remain, as does the propaganda, products of a few “stars,” but what substance exists is invisible outside its own cubicles. Intellectual substance tends to be unexciting, after all. It need not incite controversy and send people flying at each other’s throats. If education is to have a future, I conclude, it belongs to those who cultivate outsider status and successfully go independent, whether it be homeschooling their children or starting their own online academies.

I end this preamble with a warning. An outsider need owe no fealty to an ideology, including the now-dominant cult of “woke.” I am openly disdainful of this cult (and yes, it is a cult in any reasonable sense of that term). Those who find this “triggering” and refuse to read further: before you go, ask what it is that is “triggering” you? Are your “triggers” products of your certitude about the path you are on and think we should all bow to if we are to achieve “social justice”? Or is it just ideological blinkering born of lack of perspective? What are you afraid of, that you must “cancel”? Is it really just America’s “racist” or “white supremacist” past? Is it white men in the present? Or is it the free and open discourse my generation championed as we fought for real civil rights and real justice, which included opposition to foreign wars of choice and attempts to lay bare real power (which few white men have)?

Assuming you are still with me: is the recent pall of cancelation and censorship a direction you really want to continue in? Or is it a sign of worse problems than just the adjunct crisis in academia.

With that air cleared, let us begin—

(1)

“You have a call.” My father’s voice. “I think it’s that philosophy department chair.”

I grabbed the phone. “Hello?”

“Is this Dr. Steven Yates?”

It was him. “That’s me,” I said.

After standard chit-chat he got to the point. “How would you like to rejoin our department this academic year, if you’re still available. We need someone to teach three Introduction to Logic sections per semester. Are you willing to do this?”

“Am I willing?” I stammered.

It was September. I’d taught there the year before on a one-year contract, and so was a known quantity. They’d been unable to rehire me for the following year due to “budgetary constraints.” The department chair had invited me to apply for another non-tenure-track opening he’d been sure would materialize. It would be renewable for three years and could conceivably convert to tenure-track.

I’d applied on the strength of two years full-time post-graduate teaching experience, and seven publications in print or forthcoming. Four predated my PhD. I’d made an equivalent number of presentations in departmental colloquia and at conferences, one to the department where I was applying.

The hoped-for payoff: a tenure-track job. During my first three years on the job market I’d sent out over a hundred applications per year. Twelve interviews, no offers.

I’d applied for this job in May, just as the part-time position I’d held since January ended. And then waited.

June arrived, turned into July; July, into August. With calls to the department unhelpful and no other prospects — another year’s job search having crashed and burned — I’d paid the local technical college a visit. Could I “reinvent myself” as a computer programmer? I’d be bored out of my socks, but I’d be making money, and that’s what life in capitalist civilization is about, right?

Then came that phone call. It was around 8 pm, the evening before the day classes were to start.

The chair explained apologetically that one absent-minded administrator had sat on my CV all summer. The person realized at the last minute: the department needed those classes covered! There was money to pay someone $26K/year! Surprise, surprise![8]

Could I be there tomorrow?

My father was ecstatic. My wayward son, the philosophy PhD, found a job!!

Due to uncertainty about my future I’d moved back in with my parents three months before. Now I had work in my field, but was looking at a six-hour drive the following morning, assuming the weather cooperated.

Everything I’d need for a week went into my car that night: books, PC, phone, lamp, a week’s worth of clothes, a little food and kitchen utensils, toiletries, sleeping bag, some cash, financial records. Well before dawn the following morning, I high-tailed it.

I would have made it in time for my first class at 11 am, the weather cooperating and a time zone change working in my favor, had it not been for a wreck on the interstate that stopped traffic for miles for about an hour.

Needless to say, I had nothing prepared as I met with the two remaining classes. I winged it and promised the students a syllabus the next day.

Signed my contract, spent the next three hours scrambling to find a place to live. Sat crosslegged on the floor that evening under the lamp in my new one-bedroom apartment, computer keyboard in my lap, threw a syllabus together. Then crawled into my sleeping bag and passed out.

The next weekend was an exhausting venture to retrieve bed, bookcases, other furniture, the remainder of my books, stereo, and wall décor to make the place look lived in.

Thus began a productive three-year period. I published four more articles in refereed journals, a fifth in foreign translation in a Polish anthology, penned several book reviews, and had a book manuscript accepted for publication, all while teaching a full load. This was done in hopes of being first in line for that projected tenure-track opening to come. It was interesting how that opening was always one year away, but I was guardedly optimistic. The departmental chair winkingly discouraged me from applying elsewhere.

Reason for my productivity: I’d ceased spending sometimes as many as forty hours a week seeking my next job.

This all came to an abrupt halt when, at the end of those three years, I was elbowed out. There had been strong support for converting my slot to tenurable status, but not the unanimous support by the tenured faculty the university’s bylaws required.

One person had blocked the effort. That person never gave a reason. What got back to me — two years after the fact — were four devastating words:

“We can do better.”

This exemplar of academic courage had remained anonymous and been protected by the same chair who’d given me those winks. At the end, the latter spoke of a decision by “your colleagues” (plural, said while not looking me in the eye) not to offer me the tenurable position. He’d communicated this formally in a letter explaining the circumstances of my severance, thanking me for my years of service to the institution, etc., etc., ending with a paragraph containing an implied threat that any retaliatory legal action on my part against the institution “could follow you elsewhere.”

Interestingly, the letter was unsigned (I still have it).

My then-unidentified nemesis was a nonentity. That isn’t an insult, delivered from bitterness, but an accurate description. He’d published nothing during those same three years, and very little before. He’d obtained tenure in the 1960s when doing so was much easier, before the infamous collapse of the academic job market, so that mediocrity survived. There was no sign he was a classroom dynamo. Quite the opposite.

Demand for Introduction to Logic was high. The business and engineering schools both required it. I’d carried my load, revising lectures, tests, etc., based on notes I kept on what was working or not working in my classes. A definite aid for students was the old-test file I created at the university library reserve desk. My old tests weren’t copyrighted, I told them, encouraging them to copy freely. This helped me as well as them. I couldn’t use the same logic problems on tests over and over. My system forced me to think up new ones. This maintained my creative edge.

My tenured-class nemesis never allowed students to keep tests. That way he could give the same tests semester after semester, year after year, unchanged except for the further yellowing of the originals. I know this for fact; I saw the yellowed original on his desk one day. He had a reputation for indifference and even hostility to students who asked questions in class. His failure rates were high. Students didn’t learn from him. They dropped his classes if they could — and added mine!

My reputation was good, partly due to the test file and because students tended to do better in my classes. I typically awarded around six A’s per section (average size: around 35). I didn’t feel like I was inflating grades. Students majoring in subjects like chemical engineering were extremely bright in those days. They had A’s in courses considerably more difficult than mine. They wouldn’t have said I was easy, but that I was good at making abstract and potentially confusing material accessible, using illustrations and examples I had labored over from day one. There were, of course, some who took logic to get out of taking math. I wasn’t going to refuse to help them. Students came during my office hours. We worked problem after problem. Students learn Aristotelian logic through repetition, by discerning patterns in actual reasoning, and by building habits of thought they can apply to still more examples, some from other courses.

What can I say? My systems worked!

“If you take logic, get Yates, not Brown!” was the word on campus.

Doubtless this got back to my then-unknown nemesis, Associate Professor Charlie Brown (that was really his name).

There is no way around it. It was professional jealousy — territorialism, in a discipline in which underperformers feel threatened by harder-working and more successful underlings who, by any reasonable measure, are superior as scholars and in the classroom even though I did not see us as in competition (silly me). No boasting here, just statements of fact — backed up by my CV, student evaluations, and colleagues who observed me teach and commented on how relaxed and enjoyable my classroom demeanor was.[9]

Associate Professor (for two decades!) Charlie Brown saw an opportunity to eliminate a perceived threat and took it.

The experience changed me.

I had little trouble finding another position — at my home state’s flagship institution, also in need of people to teach logic. That position, too, was contingent. This time I entertained no ambitions of tenure. And no longer was I sending out truckloads of applications. As we said in the eighties: been there; done that. What I did was compile lists of what I might do when this “gig” was up: computer programmer, free-lance writer, policy analyst, editor, ghostwriter, cab driver, bartender, etc.

The test files disappeared. I was not as motivated as before.

Unhelpful was the absence of an engineering school sending over students with tremendous intellectual firepower. What I encountered instead were kids who acted entitled to good grades just for showing up.

The book I mentioned in passing came out in November of my second year at this school: a philosophical as well as policy-focused critique of affirmative action, drawing connections for the first time to the “new scholarship” then still rising which emphasized race, gender, etc., as fundamental mediating categories.[10] This, in a philosophy department that leaned culturally left, in a college of liberal arts that leaned culturally left, on an urban campus that leaned culturally left.[11] Some told me, even then, that writing such a book was a bad idea. From one correspondent: “The left will eat you alive!”

That didn’t happen, but the following April I was told, “We’ve decided not to rehire you.” There was no unsigned letter this time, and I had no way of knowing what had been said behind closed doors.

I couldn’t have cared less. I simply dug out that list of alternatives for the chronically underemployed.

It was the 1990s, and even as the economy “boomed” (i.e., the Alan Greenspan credit expansion took the Dow into the “irrationally exuberant” stratosphere and toward the Big Tech, hedge fund, etc., billionaire oligarchy of our present moment), the adjunctification of the profession went into full swing. It proceeded apace, alongside the bloating of university administrations and salaries and skyrocketing tuition. Welcome to the New World!

(2)

I spent eight years wandering outside academia except for a two-year stint earning an additional advanced degree, a public health masters, during which I assisted faculty members with research and writing. Eventually a collaborative article on health education, primary prevention, and systems theory would come out of that.[12] That piece was sufficiently outside the data-driven-study conceptual box that confines the health sciences that we had trouble publishing it.

Writing was my superpower. I believe one’s superpower is something one is born with, as a potential at least. One either discovers, learns to use, and is able to use, one’s superpower to the fullest, or one suffers and lives a “Thoreauian” life of quiet desperation. I was determined to use mine. At different periods during those years I had “gigs” with “think tanks” of various sorts, did a two-year stint writing and editing obits for a city newspaper, and ghostwrote a couple of books. The ghostwriting paid the best.

When I returned to academia, I was adjunct-zoned. This despite a book and a list of publications that had swelled to over a dozen.

Why did I return?

Good question!

I took the position partly as a favor to a friend, and partly because I had nothing better to do at the time. You can be the best writer in the world, but in a neoliberal-capitalist political economy it won’t do you any good if you can’t market it and sell it. I was no marketer or salesman, so I returned to philosophy teaching and kept writing as a hobby.

During the ensuing seven years I taught either introduction to philosophy or ethics or both (one more intro to logic class), at four more institutions spread across six campuses in as many cities and towns in the region (Upstate South Carolina). This sometimes meant commuting as much as 300 miles per week. Recall that even prior to the 2008 financial meltdown, gas prices had soared to between $3 and $4 per gallon.

I’d begun thinking about my status as an outsider, someone not in the Big Club who never would be. I was journaling about it. If this seems self-absorbed, I was the only one I knew of using this kind of situation as a vehicle for philosophizing. I had no idea what others had written on the subject, if anything. What had prepared me?

I’d written a dissertation on Thomas S. Kuhn’s and Paul Feyerabend’s philosophies of science back in those happy-and-carefree eighties, prior to my concern over such matters as employment and affirmative action.[13] Both Kuhn and Feyerabend, in different ways, stressed the “embeddedness” of scientific knowledge: in a paradigm, conceptual framework, system of description, localizable tradition, or some similar form of cultural life and the situations a culture created for its inhabitants. I had encountered Richard Rorty’s ideas as a graduate student and revisited those.[14] This had been one of the paths to postmodernity, the idea that we could not step outside our experiences and how we describe them to achieve a truly objective, “God’s Eye point of view” as Hilary Putnam called it.[15]

Indeed, historical situatedness and practice appeared to play a central role in what we call knowledge — as opposed to the Platonic-Cartesian-Kantian ideals of perfection and deductive certitude, and which positivism had reinvented for its reconstructions of logical justification in physical science. One realization that came with “historicism” was that actual knowledge-seeking and practice, process as well as justification, is considerably messier than the logical-philosophical images that had dominated analytic philosophy in earlier decades. The later Wittgenstein had risen in stature, especially during the 1950s. Kuhn, Feyerabend, and others drew on Wittgenstein’s lucid insights about natural language, perception, belief, and method.[16] There was also W.V. Quine’s criticisms of the analytic-synthetic dichotomy and his “shift toward pragmatism.”[17] Although their conclusions about science were not the same by any means, they both commented on the incommensurability of specific pairs of narratives within theories, traditions, etc., narratives being descriptions of ‘the way things are.’ This had been my dissertation topic.

From wading through a vast secondary literature it had long been clear to me: few of the critics of the “historicist” school truly understood it, and that included some who drew on it, especially “feminist-epistemology” types who sometimes borrowed ideas from Quine and Kuhn without credit. I’d come to think many who criticized Feyerabend did not want to understand him. He constituted a distinct threat, not just to dusty and arcane notions as “the demarcation problem” (between science and pseudoscience) but to something larger: a specific kind of institutionalized epistemic authority: that of scientistic-technocratic-managerialism which wore “expertise” on its sleeve, sought to apply it wholesale to organizations and to public policy, and was prepared to implement its “insights” through top-down legal and bureaucratic pressure when and where it met resistance. This was a worldview, in which academia, government, and major corporations often operated in seamless partnerships.[18]

But doesn’t, e.g., “feminist epistemology” and critical race theory come from a substantially similar place?

Yes, they share some common premises about “embeddedness,” but in their inordinate obsession with playing the role of victim, both fail to see where the real locus of power is in Western civilization. It is not with “white males” as some kind of collective. Moreover, they actually commit errors of which Kuhn and Feyerabend were incorrectly accused, which if true would have led them to a wild epistemological relativism (Feyerabend’s embrace of that label for rhetorical purposes not withstanding). “Everything is political” became the mantra of the politically correct, which meant seeing every problem through an ideological lens. This is the all-too-familiar Abraham Maslow fallacy: if your only tool is a hammer, you see everything as a nail. The “new scholarship,” moreover, impugned its critics as motivated by latent racism and sexism instead of doing what scholars had traditionally done, which was to make honest attempts to evaluate the cogency of arguments and the reliability of evidence. This, though, was too “logocentric” for the “new scholarship.” Susan Haack (the best example), though, had no trouble showing that objections to “feminist epistemology” are not political but epistemological. Ultimately the position makes no sense.[19] Philosophy’s feminists could have made far better use of their time and energy scrutinizing the political economy of academia rather than finding slights against them from the white men in their midst (unless the men were gay, of course). They still seem completely blind to the cultural power they wield.

The “historicists” never really probed the political economy of academia.

Kuhn did pen an essay on the “essential tension” between “conservative” ideas and “liberal” ones (using those terms in a broad sense), and why scientific research needs both — an idea surely applicable broadly.[20]

Feyerabend’s views were more radical, but neither did he make this a priority. While he had no intellectual use for authoritarianism in any form, he, like Kuhn and like the feminists, was in the Big Club. So not even he challenged its power substantively. He saw what he was doing as a kind of game to be played, while acknowledging its serious side: if people are suffering, do we or do we not have a moral obligation to try to alleviate that suffering if we can, by identifying its causes and working to remove them?

Today, the political economy of academia is a cause of suffering, not to mention greater deception than most people care to realize!

Few career academics look into such matters, as, say, Hernan and Chomsky looked into the political economy of mass media.[21] All appear to prefer dining around plush tables supplied by the Big Club.

Almost no one is willing to risk biting the hand that is feeding him.

Or her.

But what if, as someone not in the Big Club, you wake up one day and realize that what you are being fed, at best, are stale breadcrumbs from the academic “dinner table”?

You might as well tell the truth as you see it.

Mine started with unpleasant truths of which I had direct experience, about academic employment and underemployment.

Here is how at least some tenure-track hiring in academia (what little there now is) actually works:

A department is given authorization to create a job opening, with or without funding. A search committee is appointed. Its members, if only to save time, consult “ranked” departments and come to a tentative consensus on who they’d like to hire — or at least, on a small pool of ideal applicants. Then they place an ad in a national publication as is required by law (as is the standard EOE/AA statement), written to attract that favored person or pool.

Applications will pour in, sometimes by the hundreds. The ad will have asked for “three letters of recommendation.” That way the committee knows immediately who is networked-up. Most applicants will be eliminated after the merest glance at the signatures (“This joker has a letter from Dr. Joe Hick Farmer, Podunksville Community College. Are you effing kidding me?”).

The committee will make sure there are women and (if any applied) minorities on their short list of a dozen or so finalists. This will please the diversicrats.

The committee goes through the motions of interviewing a dozen or so applicants at a national meeting in a plush hotel in the center of a major city. Their travel is supported by the institution. Applicants attend at their own expense, often going into (or deeper into) debt. Many of the latter go without any pre-arranged interviews, hoping to land one or two.

Afterward, the committee tries to hire the person they wanted prior to placing the ad.

Or from that ideal applicant pool.

Or they go for the most qualified white woman (very few blacks are applying for jobs as philosophy teachers, and that is unlikely to change).

That’s if the position was funded. If it wasn’t, then obviously, no one is hired.

Or if the person they wanted has accepted a position elsewhere, they may “decide not to decide.” We can do better.

A “buyer’s market” incentivizes this mindset.

Pre-Internet, committees mailed out letters to rejected applicants. Some were signed; others were impersonal form letters run off on copy machines. Some cynically identified the winner by name and doctoral program. Rejected applicants, having applied in good faith, never learned that their chances of being seriously considered began at negligible and went downhill from there, especially if their letters came from academic nobodies out in “flyover country.”

Today’s era of electronic applications has depersonalized the process further. You send your materials via the university website which spits back an auto-response when your application is complete. Unless you are selected for an interview, that is typically the last you hear.

Some say all this happened because there are too many PhDs, products of a system permeated with perverse incentives. People respond to incentives. This appears to be a human constant, transcending ethnicity, gender, class, etc.

Perverse incentives, moreover, feed on each other, reinforce one another, and gather energy within a system.

Now consider adjunct faculty.

We are talking about a cadre of people who strongly self-identify with achievements such as earning a PhD, teaching, and becoming scholars — most likely in accordance with this recognition of a superpower I mentioned. This incentivizes them so that they ignore the dangers of pursuing skills few employers or consumers in a capitalist political economy want, and end up one of the “hypereducated poor.”[22]

PhD-granting programs shamelessly use this, as do hiring committees. The perverse incentive here is that the more PhDs a department graduates, for example, the greater that department’s prestige and the more prestige it brings to the university. Neither has interest in the fact that the majority of those PhDs will eventually end up working outside the field they may have spent a decade training for, and that some will end up on society’s margins, their superpowers wasted. (Some arguments against capitalism hold that it is wasteful. If it is, then academic capitalism is the most wasteful of all.)

Higher education’s dysfunction goes well beyond adjunct abuse, as I’ve implied. The perverse incentives work against fixing the problems from the inside.[23] Many of these involve money and its allocation. I was once told by a dean, “We need you but we can’t afford you.” This was at an institution with an athletic program that takes in millions per year, and which had millions to spend on new buildings and campus beautification projects. This tells me that the problem is not lack of money but a lack of priorities allocating it.

But the money problem has larger consequences than that. Money drives supposed scientific research and affects the outcomes. Under “academic capitalism” it is the strongest perverse incentive of all! Deniers of this are kidding themselves. Nearly all scientific research today depends on allocated grant moneys. Grant-givers and other donors are generally not neutral parties wanting “truth for its own sake.” Most are after something they’ll find profitable.

This explains, by the way, why research into the latest pharmaceuticals is funded lavishly while nutrition-based natural remedies and strategies for immune system building are not — and why fully a third of all televised advertisements are for legal drugs.

All of this suggests that those postmodernists who deny the “objectivity” and/or neutrality of scientific research, its ability to find “truth,” are onto something — if not for the reasons they typically give. Here the problems really are political-economic, not epistemological in the strict sense. There is a “knowledge problem,” but it is more a problem with power and funding systems within institutions, generally surrounded with the “right” language (e.g., about “the science”), becoming barriers to the discovery and dissemination of what is true. It is not a problem about “what Truth is.”

Consider all this cumulatively. Do we really have a recipe for an academia that can be trusted as a reliable repository of accumulated knowledge, know-how, and wisdom? Even in the sciences?

How could it be?

Small wonder the Feyerabends of the world grew skeptical!

One can only wonder what Wittgenstein before him would have said.

Having had eccentric personalities — which in an overcrowded job market becomes just one more reason to dismiss a candidate out of hand — were either one starting out today, neither would be considered academically employable.

It’s a given that today’s environment is radically different from what existed in the 1940s and 1950s. Despite all the technological wizardry that’s come our way since, the political-economic and cultural changes have not been for the better!

Unfortunately, we’ve barely scratched the surface here. There are opinions that are verboten in academia, whatever evidence (sometimes considerable!) can be amassed in their defense. There is “forbidden knowledge” in nearly every discipline which academics dare not dispense if they value their careers. It would take a much longer piece to explore this properly, with examples and evidence, so at this point I have to defer my discussion to the projected lengthier manuscript.[24]

(3)

It is time to sum all this up. Given what my generation and subsequent generations have through, I don’t see my case as out of the ordinary. No one singled me out. The instances of abuse I’ve talked about could have happened to anyone, and often have. I could cite situations worse than mine.[25] I’ve learned of others through the grapevine. There are multiple horror stories in circulation. Bottom line: we were all lied to, used, and treated as disposable commodities for as long as we were willing to put up with it. This will continue, because the perverse incentives permeating academia enable it, and we enable it ourselves if we maintain our determination to keep teaching no matter what it costs us personally.

There are adjunct groups I mentioned, trying to unionize and change the system from within. Good luck with that.

As for myself, in 2012, I walked away. I left the American university and went overseas. My “job title” became Independent Scholar.

While I am aware of those for whom such phrases are nothing but code for academically unemployed (or possibly unemployable, equivalent to damaged goods), to my mind, making such a move put me in the best position a thinking person can be in today. (I’d like to think I’m a thinking person!)

As an outsider I can critically evaluate academia as a whole, be it specific policies such as affirmative action, its recent embrace of the affirmative action universe’s cultish “woke” upgrade — or comment on the status of the academic endeavor as a whole and its latter-day superstitions, ideological and metaphysical. I can criticize the commitment to a materialist view of the universe (and the human person), something hard to do in academic without tenure.[26]

Outsiders can comment usefully, that is, on intellectual inbreeding; on the bullying of alternatives to dominant narratives off the academic stage, and thereby raise doubts about the presumption of the beneficence of academia as a repository of reliable knowledge and “expertise.”

An outsider can report having observed the gradual rise to dominance, over three decades, of what is now the “woke” cult, beginning with its bullying of conservative-leaning faculty back in the early 1990s (about which he warned, cf. n. 10), leading to what it is now: an aggressive, hate-filled movement far more totalitarian than anything it collectively believes itself to be displacing. An outsider can do this without worrying about being handed a proverbial pink slip and ordered not to slam the door on his way out. Yes, in my case, I’ve had to do some scaling down of my lifestyle, even being in a place where the cost of living is less than half of its U.S. equivalent. But in the 2020s, living as frugally as possible is the price tag of having a free mind.

We don’t need academia in order to think, and to write. If anything, academia needs us. Even if those in the Big Club don’t know it. That’s if they wish to avoid dishonestly providing their students with two ridiculously overpriced options: glorified job skills training for jobs a lot of which won’t exist when they graduate, or ideologically-driven zombification at the hands of the “woke” cultists.

Suffice it to say, multiple converging catastrophes have brought us to a crossroads as we enter this strange third decade of the twenty-first century. The most dangerous, in my view, is the massive consolidations of wealth and power we have seen. No, climate change is not worse, because if “reducing our carbon footprint” (or whatever) requires leviathan corporations to reduce their profits, it won’t happen. It will only happen if the corporate-state power system can remain intact, and even tighten its grip.

A precarious, disposable workforce, in addition to the personal hardships it creates, is a boon to a political economy based on centralization, concentrations of wealth, and creeping totalitarianism whatever ideological spin we put on it. It is an excellent tool for ensuring that only approved narratives are heard, because those voicing unapproved ones find themselves canceled.

This is a recipe for major civil unrest — especially if the non-recovery of the present economy becomes impossible to hide inside “cooked” government numbers. Yes, I am sure some will hold onto their delusions and tell me, “Look where the Dow is!” as if Wall Street and the real economy hadn’t been decoupled thirty years ago. Most people who buy groceries and gas are feeling massive inflation in their wallets and purses, after all. This, of course, is where a money-centered political economy keeping itself afloat exclusively with unbacked printed money eventually trends.

Returning to the adjunct crisis, it is just one manifestation of an era of mass consumption, corruption, and disposability: unsustainable in the original and highest sense of that term before it was hijacked by the sustainable-development technocrats. It has not merely impoverished at least two “lost generations” of would-have-been professors and scholars, but deprived students. For no one teaching can do his/her best when struggling with the choice of whether to pay the electric bill or the phone bill, or if again they must go hungry to feed their children when they have more month than money — perhaps also trying to pay off (or pay down) student loans!

Or worse still, if they are living in vehicles and sneaking into student dorms to shower and dress!

A final reason for my utter disdain for “woke” culties: departments and institutions, especially those filled up with such people, can virtue-signal endlessly about their commitments to “social justice,” “diversity” and “equity,” but they lay themselves open to charges of basest hypocrisy when they ignore the massive injustices and inequities happening right under their noses!

The pandemic has made matters worse, of course. A lot of higher education went online, and some of it will not come back. Students who would have returned to brick-and-mortar institutions but discovered during the COVID quarantines that they could find reliable and instantly actionable educational content on YouTube and Udemy.com might simply opt out of formal higher education altogether.

One can only hope that the future of education in the Western world has not been written. We can note the constants in play: people, including students, will continue responding to incentives, and some of their would-be faculty will continue strongly self-identifying with the ideas of teaching and scholarship. The more enterprising of the latter are also moving their activities online and going solo via YouTube channels or other platforms, or their own websites, blogs, etc. One advantage of such education for student or teacher: no administrators! (And no wokesters!)

The adjunct-zoned should be thinking along these lines. You have your computers, tablets, notebooks, smartphones, etc. You can use technology to solicit students from anywhere in the world, setting up a home office, teaching from there in your online classroom and monetizing your offerings if you are so inclined. And if you have children, not only will you find caring for them easier, but as they observe you as a role model, they will be positioned to use technology to further their learning instead of just seeing it as a source of (addictive) entertainment.

If higher education is to have a future, it will not be as the centralized, prestige-seeking, and ultimately authoritarian endeavor that dominated the landscape for the past century and longer. The future of education, if it is to have one, rests with those who embrace an outsider status and are willing and able pursue independent options. For those who do so, the future may be brighter than it seems at present.

ENDNOTES

[1] The term precariat has gained currency, as it refers to a core phenomenon of 21st century neoliberal political economy. Adjunct faculty are just one species of precariat. For a definitive account see Guy Standing, The Precariat: A Dangerous New Class (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011).

[2] The reader unfamiliar with the actual history of primary and secondary education in the U.S. who wants a quick overview of the premises and strategies that went into it might do well to consult Paolo Lionni, The Leipzig Connection (Sheridan, Ore.: Delphian Press, 1988). The most comprehensive treatment I have seen, however, is that of John Taylor Gatto, The Underground History of American Education: A Schoolteacher’s Intimate Investigation into the Problem of Modern Schooling (Oxford, N.Y.: Oxford Village Press, 2000/2001). Gatto spent thirty years in New York City’s toughest schools and won a New York State Teacher of the Year award in 1990 prior to “quitting” and embarking on the independent research program which did much to expose the true nature of the modern public schooling paradigm (it is hard to call it education). There can be no doubt he knows what he is talking about. If Gatto is not an “expert” then no one is.

[3] For the best account of the origins and development of neoliberalism see Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 2009); for more recent developments see Philip Mirowski, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go To Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown (London: Verso, 2013).

[4] Cf. Alan Tonelson, The Race to the Bottom: Why a Worldwide Worker Surplus and Uncontrolled Free Trade Are Sinking America’s Living Standards (Cambridge, Ma.: Westview Press, 2002). Cf. also Barbara Ehrenreich, Nickled and Dimes: On (Not) Getting By in America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2001); Thom Hartmann, Screwed: The Undeclared War Against the Middle Class (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006); Ian Fletcher, Free Trade Doesn’t Work: What Should Replace It and Why (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Business and Industry Council, 2010); Paul Craig Roberts, How the Economy Was Lost: The War of the World (Petrolia, Calif. and Oakland, Calif.: Counterpunch and AK Press, 2010).

[5] For this term see Sheldon Wolin, Democracy, Inc.: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008). The basic idea is that of a brand of totalitarianism that is systemic and invisible if one does not know what to look for, as opposed to systematic rulership by a visible autocrat. Inverted totalitarianism has no official doctrines or manifestos. It involves the scientistic-technocratic-managerial paradigm (see n. 18 and accompanying text) and involves an unspoken, built-in silent contempt for those it restrains who are presumed incompetent to manage their lives. Inverted totalitarianism does not exercise force at gunpoint but rather through encirclement, one might call it. It compels desirable forms of mass behavior through “nudges,” a consistent array of incentives and disincentives, slowly strengthened until noncompliance makes normal life increasingly difficult and finally impossible. A useful example to ponder in this context, currently being urged upon reluctant populations, is ‘COVID vaccine mandates.’

[6] It is actually more like the .0001 percent who have reaped the greatest benefits from the neoliberal / neoconservative axis of the past 30 years, enriching themselves still more during the pandemic.

[7] I am at work on a longer essay (still untitled) which will incorporate the present material and address these larger issues; cf. also my What Should Philosophy Do? A Theory (Eugene, Ore.: Wipf and Stock, 2021).

[8] When an administrator gives you some variation on, We don’t have the money, it is nearly always BS. If a university can pay its president a salary approaching or even in a few cases exceeding the seven figure mark; when they can spend millions on new buildings, technology centers, health clubs, and campus beautification projects; when their athletic programs are raking in millions per year, these institutions have the money. While a department chair or dean may be telling the truth that he or she lacks immediate funds to pay an instructor a living wage, this is a problem with allocation, not scarcity! Institutions have the money to pay contingent faculty living wages! Period! What they lack is an incentive structure for doing so, especially when so many of us have allowed ourselves to be abused. Cf. below.

[9] I am sure some readers will question such judgments as subjective at best, being impossible to substantiate with publicly available evidence; or dismiss much of this essay as the sour grapes of someone who did not “make it.” That would be electing to avoid the substantive issues I am raising (full versions of which will have to wait for the fuller essay; see n. 7 and 24). My preemptive responses: (1) It should be an old saw, and in a saner intellectual environment than presently exists would hardly be worth reiterating, that the motivation behind an argument is irrelevant to its validity. Attempts at armchair psychoanalysis of my motivations are therefore irrelevant and inappropriate. (2) Even so, while my experiences were what they were, no sour-grapes motivation exists. I was not forced from academia. I left by choice. I had concluded that the problems were serious and rapidly worsening, that I had no means of addressing them or even getting a fair hearing for the kinds of criticisms I wanted to make, and that eventually I would be forced out if I did not leave on my own, as some have been.

We have since crossed that Rubicon. In 2012, the year I abandoned ship, we were not yet seeing campuses disrupted by social justice warriors as they came to be called, demands for “trigger warnings” on texts, segregated “safe spaces” free from “micro-aggressions,” and finally the increasing use of white (or derivatives such as whiteness) as something shameful, to be treated with disdain and contempt: one of the central features of the cult of “wokery.” Those who displayed such attitudes then wondered why so many American whites voted for Donald Trump! All this came prior to the cancel culture of our present moment, the Orwellian ambience of censorship which, at of this writing, with Trump now out of office and calls for vaccine mandates accelerating, appears to be worsening and becoming openly totalitarian in some places (e.g., Australia)!

These matters aside, what is clear is that a labor force filled with adjuncts can do nothing to address the systemic maladies of academia, or those of the larger society, be they the administrative bloat, burgeoning student loan debt, or the disappearance of the responsible wing of the professoriate in the former, the massive structural inequities of the latter which have little to do with any actual racism that really exists, or the gathering storms of increasing technologically-imposed neo-feudalism in which the precariat as a whole (cf. n. 1) is largely helpless.

[10] Steven Yates, Civil Wrongs: What Went Wrong With Affirmative Action (San Francisco: ICS Press, 1994). The book is badly dated, offering a libertarian solution to the problems it addresses that today seem to me hopelessly idealistic. In case anyone wonders, I have no systemic solution to the problems of race in America, other than to allow peoples to go their own way, including separation if that is what they want and are able to do it without imposing their wills on others. The closest I came to a top-down solution was the reverse of one: for bureaucrats and technocrats to stop creating and imposing top-down policies by force. This is probably still hopelessly idealistic, as it calls for bureaucrats and technocrats to stop being bureaucrats and technocrats.

[11] This might be the place to note the enormous gulf between the cultural left that presently dominates academia and the economic left of yesteryear. The former emphasizes categories of race, gender, etc., and such phenomena as intersectionality. The latter stayed closer to what Marx appears to have intended, which was a focus on class directing our attention to actual power asymmetries under capitalism. The philosopher who also noticed these differences and commented that the neglect of class by cultural leftists (because the increasingly impoverished working classes and a middle class struggling under the effects of globalization were too white and too male) was Richard Rorty; see his Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 1998). Arguably, Rorty even speculated on how, given the right circumstances, a sense of loss of faith in the political economy of “democracy,” a Trumpian figure would arise. He reached this conclusion eighteen years before it happened; cf. Achieving Our Country, pp. 89-91.

[12] John Ureda and Steven Yates, “A Systems View of Health Promotion,” Journal of Health and Human Services Administration 28 (2005): 5-38.

[13] Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962, 2nd ed. 1970); Paul Feyerabend, Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge (London: New Left Books, 1975). My MA thesis (1983) was on the latter and my doctoral dissertation (1987) was on the incommensurability claims of both. I argued that what they require us to give up is the ideal of a totalizing vocabulary for all science at all places and times, not rationality or progress understood as living processes instead of Platonist abstractions. Efforts to further develop, refine, and publish these views bit the dust, unable to compete timewise with a multi-year job search often taking up as much as 40 hours per week.

[14] Richard Rorty’s signature achievement is Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979). Cf. also his Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1989). Rorty, in all probability the last philosopher of historical importance the U.S. is likely to produce, gives us much to ponder — including the consequences of the intense and excessive focus on language that has characterized Anglophone philosophy since around 1900. This is an essay in its own right.

[15] Cf. Hilary Putnam, Reason, Truth, and History (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1976), p. 49f. I eventually worked out a concept of objectivity in methodology that does not commit its user to a “God’s Eye point of view” we manifestly do not have. It is operational and goes something like this: to be objective is to take into consideration all of the relevant facts within one’s scope of awareness. The concept is obviously flexible, since relevant facts and one’s scope of awareness are always changing as the information reaching us changes, and yes, we do need some account of what counts as a fact, and what relevance is. This work remains undone, one of the casualties of a multiyear search for permanent academic employment that paid a living wage, as eventually I lost interest in the idea in the face of more immediate concerns.

[16] The later lectures and writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein dating from the 1940s up until his death in 1951, and the many posthumous publications of his various writings that followed, loom like a colossus over subsequent twentieth century analytic philosophy and emerging history and philosophy of science which stressed historical events and processes over abstract logical reconstruction. Wittgenstein was one of those rare thinkers (Rorty points this out) who produced two philosophies of great significance, the latter of which was a detailed criticism and rejection of the former. See his Philosophical Investigations (London and New York: Macmillan, 1953). The later Wittgenstein’s core ideas, that philosophical problems result from departures from our “ordinary” ways of speaking, and that the latter serve many purposes in human life, soon dominated British academic philosophy and would continue to do so for the next two generations.

For what it’s worth, it is my conviction that not only are there no Wittgensteins around today, no one even comes close!

Moreover, I do not believe his approach to language, emphasizing pragmatics (the relationship between language and language-users) over syntax (logic) and semantics, has ever been mined for its full potential. Had it been, we would have a substantial literature on how language has been weaponized, how words and phrases have been used as linguistic clubs to beat people into submission to narratives approved by politicians, corporate plutocrats, and the media elites who serve them. Conspiracy theory provides an excellent example of a weaponized phrase, invariably used in mass media, absent context or sense of nuance or subtlety, for any idea or line of questioning we peasants are not intended to pursue. For nearly all academics, the phrase acts as a strong disincentive for obvious reasons: to be labeled a conspiracy theorist is a kiss of death!

One problem is that the phrase can refer to a very wide range of allegations, from high-level crimes — researchers who cannot reasonably be accused of being nutjobs have concluded that both JFK and his brother were killed by conspiracies from within the U.S. government — to such ideas as that the moon landings never happened or that the Earth is flat, or recent movements such as QAnon, which clearly suggest mass delusion. For the former see James K. Fetzer, ed., Assassination Science: Experts Speak Out on the Death of JFK (Chicago: Open Court, 1998).

For an intellectually solid, evidence-based, fair-minded investigation of actual conspiracies in the context of the idea of conspiracy theory, whether such theories are ever valid, and the role they have played in American culture, see Lance deHaven-Smith, Conspiracy Theory in America (Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press, 2013).

[17] Willard Van Orman Quine, “Two Dogmas of Empiricism,” in W.V. Quine, From a Logical Point of View (Harvard University Press, 1953), pp. 20-46. Kuhn in particular doubtless studied Quine. Feyerabend was drawn more to Wittgenstein.

[18] For a good account of how these efforts have played out over a period of over a century now see Patrick Wood, Technocracy Rising: The Trojan Horse of Global Transformation (Mesa, Ariz.: Coherent Publishing, 2015).

[19] Susan Haack, “Science 'From a Feminist Perspective',” Philosophy 67 (1992): 5-18; Susan Haack, "Epistemological Reflections of an Old Feminist," Reason Papers 18 (fall 1993): 31-43; Susan Haack, "Preposterism and Its Consequences," Social Philosophy and Policy 13, no.2 (1996): 296-315. Cf. also C. Pinnick, N. Koertge, and R. Almeder, eds., Scrutinizing Feminist Epistemology (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003).

[20] Thomas S. Kuhn, “The Essential Tension: Tradition and Innovation in Scientific Research,” in The Essential Tension: Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), pp. 225.

[21] Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (Boston, Ma.: Pantheon Books, 1988).

[22] Alissa Quart, “Hypereducated and on Welfare,” Elle, December 2, 2014. https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/a19838/debt-and-hypereducated-poor/. Cf. also Julia Meszaros, “The Rise of the Hyper Educated Poor,” Huffington Post, January 13, 2015. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-rise-of-the-hyper-edu_b_6460180

[23] Cf. Jason Brennan and Phillip Magness, Cracks in the Ivory Tower: The Moral Mess of Higher Education (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2019). I should note that Brennan and Magness are notoriously hostile to adjunct interests, although the majority of their observations about how present-day academia is rife with perverse incentives in multiple areas seem to me valid. Ultimately their assessment of the likelihood of “fixing” the problems in contemporary academia is negative, suggesting that those of us who fled did the right thing. Brennan and Magness do not draw any consequences from their results for the presumption that academia is a reliable repository of knowledge.

[24] Still under preparation, with no definitive title as of yet (cf. n. 7 and 9). In the meantime cf. Stuart Ritchie, Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020).

[25] A fellow with whom I shared an office as a doctorate candidate landed a one-year appointment, renewable, the year I was finishing. He became a victim of blatant nepotism. The department chair and the chair’s (much-younger) fiancée did not even hide it when they elbowed their junior colleague aside and gave his job to this woman for the following year. He returned to us, unemployed and disillusioned. He was hired by a computational methods center on our campus to do programming using formal logic which was his superpower. He began applying for MS programs in computer science, was accepted into one, after which he disappeared taking his superpower with him. A good teacher, relaxed and personable in class and loved by his students, was lost to academic philosophy. One of many.

[26] For two successful example of senior scholars who have done this see Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2011) and Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2012). Cf. Philip Goff, Consciousness and Fundamental Reality (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2017) and Galileo’s Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness (New York: Vintage, 2019). I’d be remiss not to mention the work of David J. Chalmers, as Chalmers is unquestionably the leading philosopher of mind pushing the envelope against materialist supremacy, one might call it; cf. his The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1997).